Some names have been altered to protect the identities of the unhoused.

The Reality

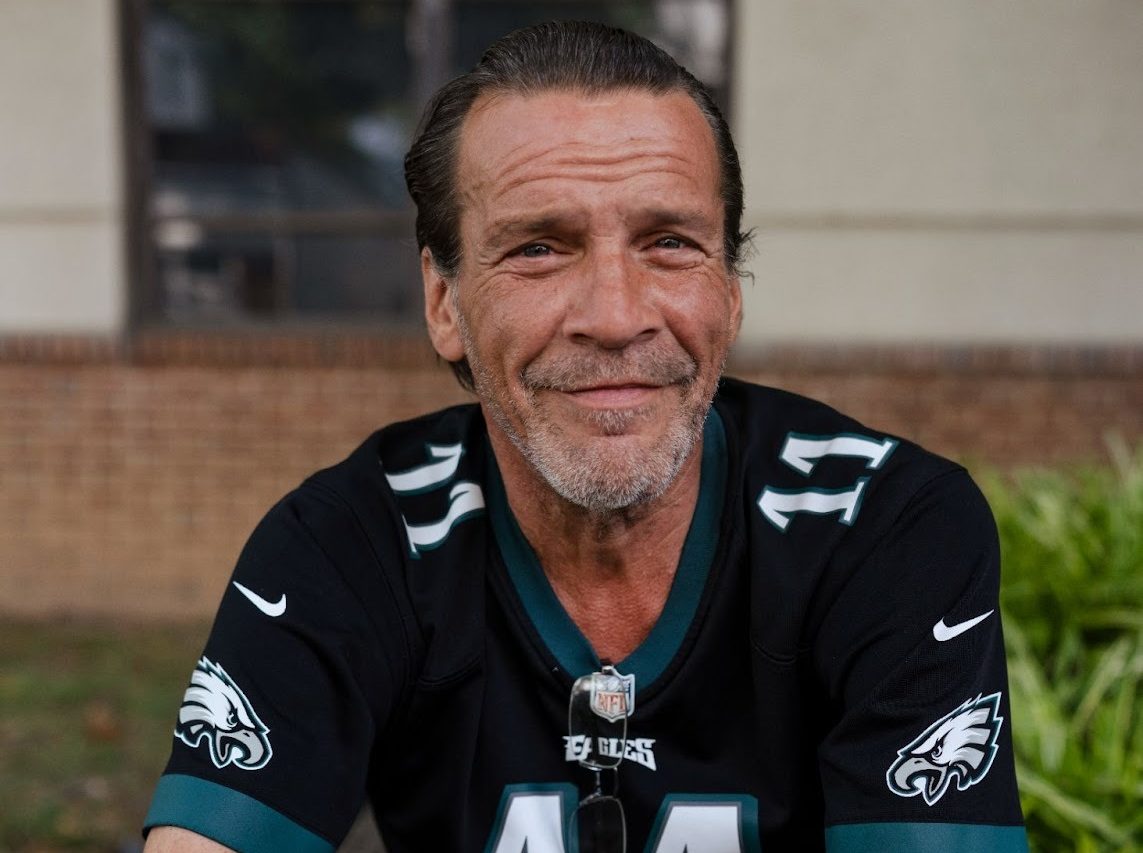

(Philadelphia) Sarah and Jared remember the first nights after they lost their housing as a period defined by fear. They worried that their two teenage sons would be ridiculed at school when classmates learned of their homelessness. The boys tried to hide their situation, but the signs were there- overworn clothes and bone-deep fatigue revealed the strain they were carrying. Jared worried that the disruption would cost him his hourly warehouse job, or that shelter rules would separate the family at a moment when they were under intense strain. The family had already been through more than they imagined they could carry: Sarah was undergoing cancer treatment at the time, and medical bills had pushed the family behind on rent. As their housing costs became untenable, they entered a shelter system they had never imagined needing. Now they worried not only about Sarah’s cancer diagnosis, but also where they would sleep and how long they could keep their family’s life from further unraveling.

That fear eased when the family was placed into housing through a Housing First program. With rapid rehousing assistance, they were able to move into an apartment of their own within weeks. The subsidy covered part of the rent for a limited period, enough to stabilize the household while they regained footing. Once housed, Sarah was able to focus on her health and resume treatment without the daily uncertainty of shelter life. Even after Jared later lost that job, the family remained housed, adjusting their budget and searching for new work without the immediate threat of displacement.

Housing First

Their experience reflects how Housing First operates nationwide. For more than two decades, the federally funded framework has guided how federal, state, and local governments respond to homelessness, providing different forms of housing assistance depending on need. Families and individuals facing short-term financial shocks—such as rent increases, job loss, or medical expenses—are often served through rapid rehousing, which offers temporary rental assistance tied to permanent leases. People with more complex needs, including disabilities or chronic health conditions, are more likely to receive permanent supportive housing—long-term housing aid paired with ongoing, voluntary support services such as health care coordination, substance use treatment, benefits enrollment, or employment assistance.

Housing First programs serve hundreds of thousands of people nationwide each year. As rents have climbed and wages have stagnated, an increasing portion of those households are working adults and families who lose housing after a short-term financial shock. Studies have consistently found that most participants placed into housing through Housing First remain stably housed one year later, at rates that exceed those of shelter-based or treatment-first systems—supporting the model’s focus on early intervention before a temporary crisis becomes long-term homelessness.

In recent months, the Housing First framework has come under legal and political challenge. The Trump administration proposed changes that would significantly curtail federal support for permanent housing programs, placing housing stability at risk for more than 170,000 people currently served. Under the proposed framework, funding would shift toward what HUD refers to as the Continuum of Care—the network of emergency and transitional services designed to manage homelessness once it occurs. This includes emergency shelters, where people typically stay night to night; outreach teams that connect people living outdoors to services; transitional housing programs that provide temporary placements with strict time limits and program requirements; and the local agencies that determine eligibility for limited assistance.

A coalition of states, local governments, and nonprofit organizations has sued the federal government, arguing that HUD’s proposed funding changes unlawfully undermine Congress’s directive to prioritize permanent housing and Housing First approaches. The lawsuit asserts that the administration is attempting to rewrite federal homelessness policy without legislative approval.

In response to that challenge, a federal judge in Rhode Island blocked the Trump administration from moving forward with proposed changes to homelessness funding—but the ruling stopped short of permanently resolving the dispute. The judge issued a preliminary injunction, a temporary order that prevents the Department of Housing and Urban Development from enforcing the new funding conditions while the lawsuit continues. For now, HUD is required to operate homeless assistance under its existing rules, which prioritize permanent housing and Housing First approaches.

For people who have relied on rapid rehousing to escape homelessness, the proposed changes raise fears about losing the support that made stability possible. Danielle, a Philadelphia resident who entered rapid rehousing after fleeing domestic violence, said the program allowed her to move from a shelter into her own apartment—a shift she described as transformative. “Getting housing was a turning point for me,” she said, explaining that having a place of her own made it possible to begin rebuilding her life.

Kiera, another former Housing First participant, said the assistance arrived at a moment of acute crisis. She described cycling through instability before receiving housing support and said the program was essential to her survival. “It saved my life,” she said. Now, she added, she worries about what will happen if rapid rehousing is cut, not just for her, but for others still trying to find their footing.

Supporters of Trump’s proposed changes argue that Housing First has failed to curb rising homelessness and that federal funding should place greater emphasis on treatment participation, employment, and measurable progress toward self-sufficiency. They contend that providing housing without mandatory participation in services does little to address underlying issues such as substance use, mental illness, or long-term unemployment, and that federal dollars should instead incentivize compliance with treatment and workforce programs.

Housing First programs, however, do not reject services. Under the permanent supportive housing model, housing is paired with voluntary services—including behavioral health care, substance-use treatment, and employment support—that residents may access if and when they choose. The central dispute, then, is not whether services should accompany housing, but whether access to housing should be conditioned on participation in those services.

Housing and Urban Development Secretary Scott Turner has framed the shift as a move toward “accountability,” saying homelessness programs should prioritize outcomes such as treatment completion and workforce participation. Some Housing First proponents counter that this accountability framework revives outdated assistance eligibility models that grouped people into two categories: those deemed compliant enough to merit assistance and those who were not- shifting attention away from structural drivers of homelessness, such as rising rents and low wages, and back onto individual conduct.

Housing advocates say defunding permanent housing programs would have immediate and cascading effects on already strained homelessness systems. When long-term housing assistance is reduced or destabilized, people who lose housing often cycle back through emergency shelters, emergency rooms, and other crisis services—systems that are already operating at or near capacity.

Each year, HUD’s Point-in-Time count—a nationwide snapshot of homelessness on a single night—shows that the United States has roughly half as many shelter beds as people who are unhoused, a gap that leaves large numbers of people without any temporary place to stay. The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report found more than 770,000 people experiencing homelessness on a single night in January 2024 — underscoring the scale of need relative to shelter capacity. With no viable shelter alternative, more individuals and families have been forced to live in vehicles, encampments, and other unsheltered locations.

“We see the impact almost immediately,” said Luke Stivala, program Director of the Breaking Bread Community Homeless Shelter. “People who had been stably housed for years come back in crisis. Their health deteriorates, they lose access to medication, and they end up cycling through shelters, hospitals, and sometimes jail. From inside the system, it’s very clear: housing is what holds everything together. When it’s taken away, the damage spreads fast.”

Researchers explain that homelessness trends are driven primarily by structural factors, including chronic underinvestment in affordable housing, wages that have failed to keep pace with rents, gaps in health care and the social safety net, and the long-term effects of mass incarceration.

They also note that while Housing First programs show high housing retention rates and reduced use of costly emergency services, funding for those programs has not kept pace with the scale of need. The problem, they argue, is not excessive reliance on Housing First, but insufficient investment to meet demand.

Sarah, when considering the possibility of Housing First’s defunding, said she thinks often about what would have happened if that assistance had not been available. “I think about families like ours who fall into homelessness and don’t get that chance to catch themselves,” she said. She also worries about people with disabilities or chronic illnesses who rely on permanent supportive housing to remain stable. “Once you know how fast things can unravel,” she said, “it’s hard not to think about who won’t have that support when they need it.”

Leave a Reply